You taught together at Rollinsford Grade School for several years. What approaches to learning have been meaningful to you in your careers?

SHERYL: When I started my teaching career I was in a large city school. As a new teacher, it was beneficial to be using a curriculum that set the pace for the year and made sure the scope and sequence was all-encompassing. But the tricky part of this was not having the flexibility to slow down and focus on an idea or strategy to give students a better understanding of a concept if they were struggling. The thought was that you had to just keep going and eventually they would get it. In math, for example, the curriculum looped back around multiple times throughout the year, so students would get another chance to deepen their understanding. But in the meantime, students could be left frustrated and feeling inadequate since they knew they weren't getting it and the class was just moving on regardless. Another challenge was that there was very little room to delve into a topic that was of high interest to students if it wasn't part of the set curriculum. This was very frustrating for me, and one of the reasons I eventually decided to start looking for another way to teach.

I left the large school for a position at Rollinsford Grade School teaching in a multi-age classroom for the first time. The benefit for me was that Rollinsford was an inquiry-based school so I was encouraged to teach topics of high interest to my students. This was exciting for me-- and yes, a little scary! It was definitely harder and more time consuming, but it also had a high reward for the students as far as engagement, excitement, and discovering how to love learning.

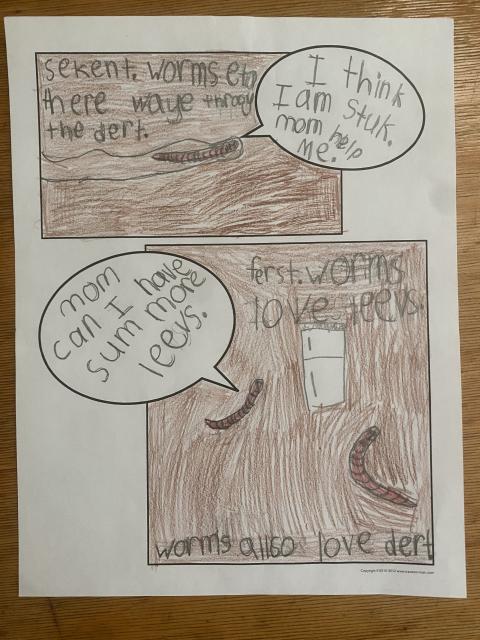

Rollinsford used investigations for the backbone of their math curriculum, but you could essentially design your curriculum the way you wanted and pull in other rich math tasks to enhance the learning. If your students were struggling with a concept and you needed to slow down, you were allowed to do that. I was also able to get my students outside and study the environment, noticing what was happening in the world around us. I found out about the Trout in the Classroom program and got multiple teachers from both the first and second grade and fifth and sixth multi-age classrooms on board. We went through training for Trout in the Classroom and New Hampshire River Fish provided by NH Fish and Game, and then we started our year exploring what fish and macroinvertebrates live in the Salmon Falls River, which was just down the street from the school. We set up a large tank to mimic the river flow and collected fish to observe and study throughout the year. The fifth and sixth graders and first and second graders worked together, taught one another what they were learning at their prospective grade levels, and grew as a learning community. It was a very special year!

DEB: It’s a lot more work to teach this way-- it’s so much easier to just open the textbook. But that was why we taught there. We wanted to be able to teach using inquiry. We taught using inquiry when it made sense, and we always followed a clear scope and sequence. That's what made teaching unique. Once there was a principal who came in and ordered us all science books, and they sat on the shelves because that's not how you teach science.

Tell me more about the inquiry-based approach. What does that entail?

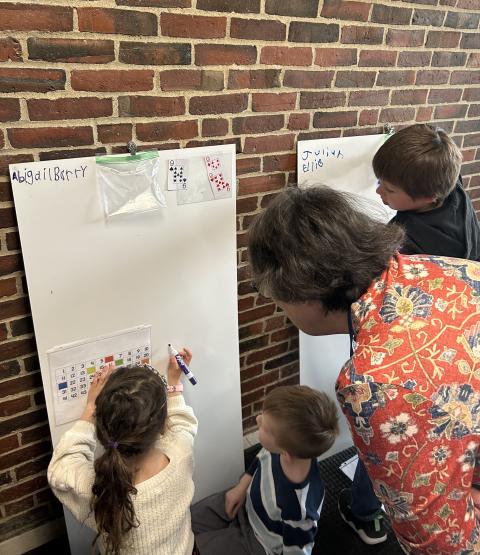

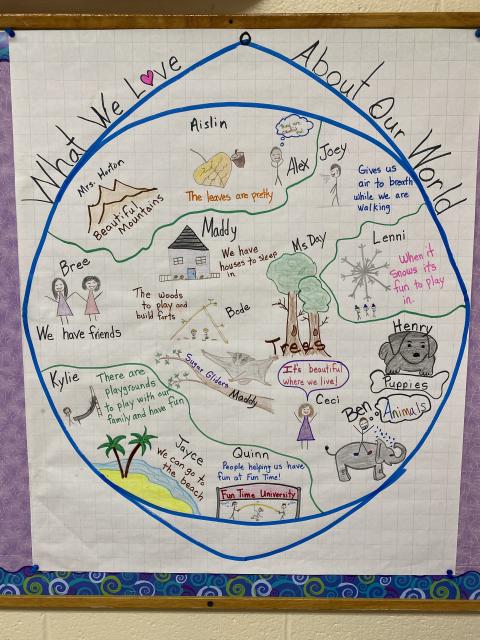

DEB: With inquiry-based learning, the kids have voice and choice over what they’re going to learn about. And it’s hard! Keeping up with so many different things can be overwhelming, but the students are invested in what they’re doing. The excitement is there.

I get so frustrated when learning becomes rote and mimicking. It's not learning, it's just regurgitating somebody else's information. I know there are two sides to every story. Kids come from all kinds of different backgrounds, and they don't have the same basic knowledge. I get it. And not every teacher is going to take the amount of time that you really need to if you're going to teach using an inquiry-based model. But boy, what a difference-- really, truly what a difference-- it makes when the kids have some say. Do I think that they need guidance? Absolutely. If we're going to study about plants, let's have a plan so that we aren't all doing the same thing every year. But let's let the kids choose the parts. Is it nutrition? Is it gardening? Whatever it is, let's go from there.

SHERYL: As early educators, our job, first and foremost, is to engage with kids in such a way that they love to learn. You can't teach young children something if they aren’t interested, if they don't understand the value of learning or if they don't think that it's fun. It’s your job, if you're teaching kindergarten, first or second grade, to get kids to love coming to school. Honestly, I feel like if they don't love learning by the time they've hit third grade, you've lost them. They aren't going to become the educated adults that you want them to be because they aren’t going to be invested in their own education. That's my personal opinion. I think early elementary school is where it starts: you have to grab them and get them to love being at school every day. They have to value it, and that rises above anything that you teach them. Of course what you teach is important as well, but you need to do it in such a way that they love learning itself. That they understand the value of the process and get excited when they discover something new.

It’s also imperative to get them to understand the value of having a community of learners that they can have fun and grow with, feel safe with, feel listened to while also listening to the ideas of others, and with whom they can work out their differences. The social piece is so central to creating a welcoming, safe learning space.

Did this inquiry-based approach lead to any particularly memorable learning experiences for the students?

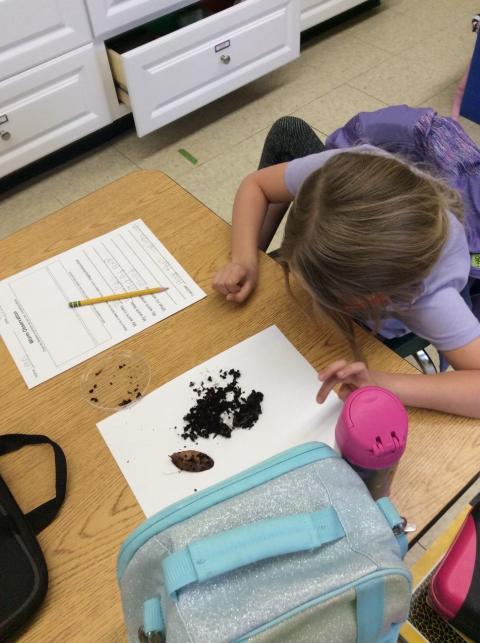

SHERYL: The whole point of inquiry-based learning is that you follow the student's lead. Sometimes you don't know what you're teaching, and you're learning with them. I can remember that when I first started, I was terrified not to know everything about the lesson. Our principal at the time said to me, “Sheryl, you just have to jump.” I had this student—she was on fire! She was looking at this nonfiction book on growing plants one day and said, "I want to learn how to grow something!" Alright, I thought, this is where I jump in.

I went down to the Agway store in Dover and said, "Do you have any suggestions for me? Here's what one of my students wants to do." And "Mr. Agway" said, "A lot of farmers are learning about the benefits of feeding fodder to their livestock right now as opposed to just grain. I think you could grow fodder really easily. Perhaps you could research why this is happening, what it is, and how to grow it?”

Next to the school, there happened to be a woman who had a horse. We could almost see it from the classroom. So I knocked on her door and told her about our new endeavor. I asked her if, after our fodder had sprouted, we could come over and teach her about it and see if her horse would eat it? And she said yes! So our class grew fodder. We learned all about it and why people were experimenting with feeding large herds of animals this way. On our big day, each student carried their note card and their bucket of fodder over to our neighbor's yard and got into this big circle. They then took turns sharing this new knowledge with her. They each got to pet the horse, and then we presented our fodder to the animal, who wanted nothing to do with it! But anyway, that's an example of inquiry with my class during my first year at Rollinsford.

DEB: Wouldn't you want your child to learn like that? Our school is a model of what schools can be. I'm thinking of all the parents who are pulling their kids out to be homeschooled now, and you know what? They're doing very similar things to what we’re talking about. Are the teachers trained? Not necessarily, but the kids are getting a type of learning that is not just turning the page but is based on inquiry—finding out what the students want to learn and diving in.

There are times when, if I had grandchildren, I'd say, "You know what, I want to homeschool them, too. I want them to find joy in life and joy in reading and sharing and wondering.” I think that in some places, that gets sucked out of school, whether by staff, the school administration, or the Department of Education dictating what you teach.

The goal is to get kids excited. If you can't rope them in and get them excited about learning, why would you even want to be a teacher? What joy does it bring me to have somebody telling me what I have to teach when they don’t even know my students? If I'm teaching a prescribed curriculum, I'm teaching the program, not the child. It's so sad to see.

What brought you to teaching?

SHERYL: Teaching was my second career. I didn’t start as an educator. When my own kids were little, I went back and got my degree to teach. Prior to having children, I was a Habilitation Specialist working with handicapped adults. Then I started my family and became a full-time mom. After I had my second baby, I found a program called Parents as Teachers. It was a birth-to-five program where people would come in and do activities with the parents and children each month. There were home visits, playgroups, and lots of resources. I joined as a mother and loved it. The program's goal was to identify children who had delays in development, like gross motor skills or speech, before they entered kindergarten. The idea was that by addressing these needs early, children would progress in their development much faster, with many no longer needing services when they entered kindergarten.

The program began to grow, at which time I took a part time position as a parent educator. I loved the role, got to work with some amazing people, and really enjoyed spending time with families. One of the other parent educators was a retired teacher. She saw my passion for early childhood education and said to me one day, "Sheryl, kindergartners would love you! You should be teaching." Her encouragement stuck with me. So when my youngest child went to kindergarten, I went back to school myself and got my teaching certification.

Deb, what was your path to becoming a teacher?

DEB: When I was younger, women didn't have, or weren't aware of, all the potential careers they could pursue. So nursing or teaching was generally what most people did. And when I was five, my mother saw me teaching my sister how to tie her shoes and said, "You'd be a good teacher." That memory stayed with me.

I married young. My husband and I put ourselves through school. It took us seven years. We both had jobs and worked our way through, going part time. Then when we moved up here, he got a teaching job right away and I didn't. I had worked so hard. I ended up taking a job at Oyster River Elementary as an aid. And then part way through the year, they needed a teacher at Rollinsford.

I found out I was pregnant the day of my interview. I told the principal, and he said, "We'll take you in any condition." So I went to the interview and, of course, I was hired. I had to find a sub for six weeks. That's all you got off, six weeks to the day. My daughter was born in February, and starting in May I began working a second job—nights, waitressing—because we didn't have enough money to pay for diapers and all that kind of stuff. I was earning $8,800 a year and loved every second of it. And I've been there ever since.

I mean, it hasn't always been wonderful, and there have been ups and downs. It's been 44 years at the same school, and I tried to leave twice, but then things would shift and so I stayed.

What has changed in education since you first started teaching?

DEB: I don't think it's the kids themselves who've changed, I think it's the parenting. The needs of families has changed as well, and the culture. There's not as much follow-through these days. On the other hand, kids today are definitely more worldly. Back in my day, I had students who'd never even been to Dover or our state capital! We'd take a trip to Boston and it would blow their minds. Now, kids travel all over the world, which is fantastic. They're exposed to so much more and have a much broader perspective.

SHERYL: I also think kids are being exposed to things they never used to see: more violence on TV shows and the types of video games that they're playing. That has had an effect on how they treat one another and what we see in the classroom and in the schoolyard. I think one of the most challenging parts of the day for some students is navigating issues outside: compromising with peers, making sure everyone’s voice is heard, playing fairly. The outside space often just has a few people monitoring a large playground with a lot of kids. When students enter the classroom again, the next 15 minutes is often full of upset students wanting their teacher or the guidance counselor to hear their side of a story and help them to resolve a conflict.

I think one of the other things that we struggle with at school is that children don't have the opportunity to learn how to share or negotiate. A good example is that when I was growing up, we had one TV in our whole house and did a lot of compromising on what we watched. There were five kids, and we didn't all want to watch the same thing. We negotiated constantly! Today, many families have multiple TV’s and lots of other devices to watch shows or play games on. Oftentimes, kids are watching different shows on different devices at the same time. No negotiating necessary. And also no conversation about what is happening on the show, how the characters are interacting, or things like that. They are each doing their own thing. No social skills required.

At school, suddenly it's all about community--sharing, taking turns, cooperating. But this concept might be unfamiliar because they haven't had to practice it at home. Perhaps with the rise of remote work, some parents, even though they're physically present, aren't as engaged with their children's daily lives. I think that a lot of screens are just babysitters. And while we can all understand the need for this at times, if it happens regularly, the result is not so desirable.

DEB: They also don't always eat at the table anymore. That dinner time is gone. I've had kids tell me that they eat dinner in bed because that’s where their TV is. I love working on and developing vocabulary with kids. And that's where a lot of vocabulary used to come from; you ate dinner together as a family. You ate breakfast together. You sat at a table and conversed and, at least in my family growing up, your TV was off when you sat at the table. It wasn't background noise or anything, it was off. And I don't think that happens so much anymore. I think it's rare now that families sit together nightly and have a meal together. There's so much else going on and it's not necessarily a priority for every family. But it changes everything: family dynamics, learning, vocabulary. And it changes a kid’s attention span, their give and take, their listening skills.

What advice would you give to someone entering the profession now?

SHERYL: My son entered the profession three years ago. He was hired to teach French at the ninth and tenth grade level, and he says it's the hardest thing he's ever done. He spends a lot of time talking with me about his frustrations. He loves being in the classroom, he loves teaching the kids, and he loves his colleagues. But he says, "there's so much wrong with this—it shouldn't take me this many hours to do a job. I'm making far less money than most of my friends and I work twice as many hours!” Two people who graduated with my son have already left the teaching profession. One of them told her mom, "This is crazy! Why would I do this for the rest of my life?" And it has nothing to do with teaching. They loved teaching, but it’s the other demands on an educator's time. You don't get extra time to do your grading or reporting or parent conferences or meetings about students with behavioral issues. There are so many more behavior issues than there were when I started teaching.

I have told my son, "You lived with me. You know what my life was like. And at my age, I'm telling you that you have to find a different way. It’s not healthy. You know that. You need to figure out how to balance it. You need to figure out how to say no. Decide that you’re not going to work every night—that what you do during the day has to be enough.'"

So my advice to him, and to anyone else, is that you have to figure out how to find balance in your life.

DEB: I retired the year before the pandemic. I remember sitting at home, looking out the window, saying, “what are you waiting for, to die?” Seriously. I said those words out loud. It was like I had nothing else in my life because I gave every ounce of energy to teaching and raising my two kids. I never got a chance to find joy or passion outside of teaching. Taking care of myself wasn’t a part of any of it.

But to this day, when I hear people saying, “nope, I'm not going to do that anymore, or I'm not going to learn this,” there's still something inside of me that says, but you’ve got to. But I know that they have to set healthy boundaries for themselves.

At one point I told my daughter, “don’t. Don't become a teacher.” But now I have some qualifiers. I say: have another plan, just in case, and search for the right environment. If you have to go into an environment that isn’t healthy, not just physically but emotionally, you need to take care of yourself first. So have another plan. But I don't want to say not to become a teacher because it's brought me so much joy, so much learning and so many friendships and a second family—a second home. All of that. And at the end of the day, I'm so glad I did it.